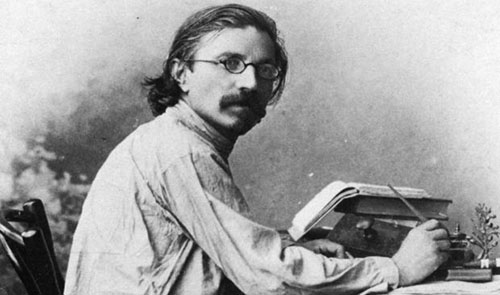

Шолом-Алейхем прийшов у літературу молодим і повним творчих задумів і… мав непростий характер. На той час єврейська література існувала і мала свого читача, і, зрозуміло, молодий Соломон Рабінович, який став надалі Шолом-Алейхемом як компроміс одруження та отримання багатої спадщини, розумів труднощі завоювання свого читача. Інакше кажучи, ніхто не чекав якогось невідомого молодого автора зі своїми принципами з розкритими обіймами в єврейській літературі.

Почав писати Соломон ще в юному віці, заради забави, не думаючи про літературну кар’єру. Стаючи старшим, він не втрачав захоплення літературою, відточуючи свою майстерність, шукаючи себе в літературі. Забігаючи далеко вперед, ми знаємо, що йому це вдалося. Але від початку читачі і критики були до нього прихильні.

Перечитуючи щоденники та листування Шолом-Алейхема, ми виявляємо його нарікання на несправедливість літературної спільноти. Цікаво, що він став відомим не завдяки своїм серйозним, об’ємним творам, а одному нехитрому оповіданню.

У 1887 році у «Фольксблат» було опубліковано «Ножик» – розповідь про хлопчика, який мріяв про ножик, не стримався і вкрав його у постояльця, а потім замученого совістю. Проста на перший погляд історія, кумедна та сумна одночасно. З “Ножика” і почався відомий письменник Шолом-Алейхем (1859-1916).

Шолом-Алейхем, «До моєї біографії»:

«Мої писання, однак, у ті часи були не більше ніж забава, доки не трапилася історія з «Ножиком», яка змінила характер моєї творчості, як і моє життя. У ті дні мене займала комерція – гроші, біржа, цінні папери тощо, які не мають жодного відношення до літератури. Я досяг тоді вершини свого добробуту, мав великі гроші і, можливо, пішов би іншим шляхом, тим шляхом, який деякі вважають справжнім. Але сталося інакше.

Якось приїхавши до Києва з різних важливих справ і втомившись за день, я ліг спати, але заснути не міг. Підвівшись, я присів до столу і написав, точніше, виклав душу в розповіді про свої дитячі роки, якому дав назву «Ножик». Написане я відправив до редакції та забув про нього. І ось одного разу читаю «Схід» («Книжки Сходу» – єврейський щомісячний літературно-публіцистичний журнал російською мовою, що виходив у Петербурзі у 1881-1906) і бачу літературний огляд за підписом «Крітікус» (псевдонім Семена Дубнова – єврейського історика згодом автора «Всесвітньої історії єврейського народу» в 10 томах, що вийшла в 1925-1929), який серед будь-якої нісенітниці згадує і про мій «Ножик». Зі страшним серцебиттям прочитав я кілька теплих рядків Критікуса. Він хвалив мій «Ножик» і стверджував, що молодий автор виявляє талант і згодом подарує нашій бідній літературі розмовною мовою ідиш гарні твори. Сповнений подяки, зі сльозами на очах, я ще раз перечитав ці слова милого Критікуса і дав собі слово писати в цьому роді ще й ще».

Так маленьке оповідання вказало Шолом-Алейхему його шлях у літературі, і світ отримав великого єврейського письменника.

Роком раніше, наприкінці серпня 1886 року, став опікуном багатої спадщини дружини, Шолом-Алейхем на зборах київських єврейських письменників оголосив про намір видавати власний літературний альманах на ідиші, в якому «збере всі найкращі єврейські літературні сили». Таким чином, Шолом-Алейхем-письменник став ще й Шолом-Алейхемом-видавцем. Це і стало джерелом конфронтації письменника-видавця з іншими письменниками.

У листі до письменника і близького друга Якова Дінезона Шолом-Алейхем написав: «Я розшибу голову публіці тим, що одного прекрасного ранку раптом вийде у світ велика єврейська збірка, та така, якої світло не бачило, але без оголошень, без барабанного бою, без дзвони, без виманювання грошей, без премій, але – з оригінальною програмою, з твердо встановленою оплатою співробітників, з доступною ціною, з усіма перевагами, з усіма привілеями; загалом, брате мій, це буде щось особливе, таке, чого і давньоєврейською не було. І уявіть собі – це подобається публіці, протягом двох тижнів я отримав уже більше половини матеріалу. І що це за матеріал! І від якихось письменників! Від якихось єврейських письменників! Товар найвищої марки. Перші звістки про нього з’являться, коли збірка буде повністю готова; за грошима зупинки немає, і дзвонити мені ні до чого…»

У листі Шолом-Алейхема до Лінецького ми виявляємо програму та завдання його літературного проекту:

«Ціна – найдешвша, щоб ощасливити багатьох.

Затія моя зроблена не заради прибутків, а на славу єврейської мови.

Програма буде такою, якої не згадають з часів Адама.

Вона міститиме все, включаючи пташине молоко.

Запроваджується систематична критика того, що виходить єврейською мовою.

Якщо десь є єврейський письменник, і вартий, він мій.

Плачу (і, що називається, чистоганом) за кожен рядок від 2 до 10 копійок за прозу, від 10 до 20 – за поезію.

Хочу вигнати манеру експлуатувати автора за допомогою лестощів.

У першій збірці я дам оригінальні статті різних письменників, що пишуть єврейською, а також гебраїстських (тобто пишучих на івриті) і російських письменників у перекладі єврейською мовою, цілі, не дуже великі оповідання, новели, поеми, один роман, трохи віршів (і добрих), а також різне з усіх галузей знання та з галузі мови.

Про медицину, гігієну, страви, напої тощо теж буде».

Перший номер альманаху «Ді юдіше фольксбібліотек. Єврейська народна бібліотека. Збірник статей літературних, критичних і наукових» Шолом-Алейхема вийшов наприкінці літа 1888 обсягом 616 сторінок і мав три розділи: белетристику, критику і публіцистику. Багато авторів, які писали на ідиші, надіслали Шолом-Алейхему свої статті, повісті, оповідання, вірші. Альманах було надруковано в друкарні Я.Г. Шефтеля у Бердичеві. Вартість одного екземпляра на той час була досить великою – 1 рубль 35 копійок. Читачі прийняли «Єврейську народну бібліотеку» дуже добре: лише у січні 1889 року за передплатою було розіслано 2000 екземплярів. Всього Шолом-Алейхем встиг видати лише два своїх Альманахи.

Шолом-Алейхем чудово впорався із завданням випуску Альманаха. Йому вдалося залучити відомих тоді авторів для публікації їхніх творів: повість «Заповітне кільце» Мойхер-Сфоріма, балада «Моніш» Іцхока-Лейбуша Переца (написана спеціально на ідиші, хоча до цього Перец писав лише на івриті), мемуари поета та публіциста Готлобера та багато іншого.

Сам Шолом-Алейхем у своєму альманаху виступив як романіст («Стемпеню»), критик (стаття про Гейна і Бернса) і публіцист (статті «Російська критика про єврейський жаргон» та «Кілька слів про орфографію єврейської мови», підписані «Видавець») .

Вихід у світ альманаху «Єврейська народна бібліотека» сподобався освіченій єврейській публіці, привернув увагу одних єврейських авторів можливістю заробітку публікаціями, а інших налаштував проти Шолом-Алейхема.

Шолом-Алейхем показав себе твердим і важливим редактором. Він бачив своє видання художньо якісним, встановив високі гонорари, і… нажив собі ворогів у єврейському літературному середовищі. Колеги-письменники не злюбили його за неузгоджені виправлення у їхніх творах. Серед таких ображених були Мойхер-Сфорім, Перець, Лінецький, Готлобер.

Заради справедливості слід сказати, що Шолом-Алейхем редагував і себе. Він п’ять разів переписав свій роман “Стемпеню” для публікації в Альманасі.

Так, Шолом-Алейхем-письменник увійшов у конфлікт із Шолом-Алейхемом-видавцем. Крім цього, також виник Шолом-Алейхем-критик, досить суворий, і це ще більше налаштувало проти нього побратимів по перу.

Того ж 1888 року Шолом-Алейхем опублікував у додатках до «Фольксблату» цикл критичних статей про твори популярних тоді єврейських письменників – Мойхер-Сфоріма, Спектора, Лінецького, Мордхе-Арне Шацкеса. Однією з таких статей була “Тема злиднів у єврейській літературі”, в якій Шолом-Алейхем проаналізував проблему пошуку основної ідеї єврейської літератури.

Також у 1888 році, відчувши власну вагу в літературному бізнесі, Шолом-Алейхем видав брошуру-памфлет під назвою «Суд над Шомером, або Суд присяжних над усіма романами Шомера, застенографовано Шолом-Алейхемом» (надруковано в Бердичеві – там же, де його Альманах).

Хто такий був Шомер і за що він удостоївся критики Шолом-Алейхема?

У 1880-ті найпопулярнішим єврейським письменником на ідиші був Нохум Меєр Шайкевич, який писав під псевдонімом Шомер. Його невигадливі, але сповнені неймовірних ситуацій та пригод бульварні романи подобалися єврейським видавцям та читачам усієї «смуги осілості». І Шолом-Алейхем почав розкривати «кухню» виробництва таких бестселерів.

Шомер та інші єврейські автори «смуги осілості» брали за основу популярні французькі бульварні романи, замість французьких персонажів вигадували містечкових євреїв. Сюжетні лінії будувалися за французькою калькою: любов, розлука, підступні суперники, вірні друзі, загадкові злочини, а в результаті, після всіх випробувань, містечкові євреї виявлялися дітьми вельмож та багатіїв. Тобто був обов’язковий хепі-енд.

Таких бульварних романів видавалося багато. Один тільки Шомер в одному тільки 1888 році опублікував 26 книг. Тиражі досягали десятків тисяч екземплярів, містечкові євреї, живучи в сірій реальності, насолоджувалися такими красивими, надуманими історіями та чекали на наступні історії. У Шомера та йому подібних авторів єврей обов’язково розбагатіє, тоді як у Шолом-Алейхема єврей – це містечковий бідняк, якому багатство не світить.

Зрозуміло, серйозні письменники, такі як Мойхер-Сфорім, Перец і, звичайно, Шолом-Алейхем були незадоволені таким солодким, надуманим отруєнням свідомості єврейського читача.

Повертаючись до памфлету Шолом-Алейхема «Суд над Шомером», визначаємо його своєрідним викликом авторам легковажних книжок. Витяг з першого розділу «Обвинувального акту»:

«Найбільшим, найплодючішим і найбагатшим з усіх цих тарганів, жучків і черв’яків є великий «романодел», наш підсудний Шомер.

Цей молодик взявся не на жарт затопити єврейську літературу своїми неможливими, водянистими романами, своїми дивовижними творами, що стоять нижче за всяку критику. Вони, безумовно, шкідливі читачам, як отрута, бо перекручують його найкращі почуття жахливими небилицями, дикими думками, несамовитими сценами, про які єврейський читач раніше не мав жодного уявлення.

Це здалося дивним нашим представникам. Було виділено комісію. Обстеживши півсотні романів Шомера, вона дійшла таких висновків:

а) майже всі вони просто вкрадені з інших літератур;

б) усі пошиті на один крій;

в) романоділь не дає реальних, справжніх картин єврейського життя;

г) тому його романи до нас, євреїв, жодного відношення не мають;

д) ці романи лише засмучують уяву й ніякого повчання, жодної моралі надати неспроможні;

е) вони містять лише словоблуддя та цинізм;

ж) вони, крім того, дуже погано складені;

з) автор, мабуть, невіглас;

і) школярам і дорослим дівчатам у жодному разі не можна давати цих романів;

к) було б великим благодіянням викурити його разом із усіма його дивовижними романами з єврейської літератури з допомогою конкретної систематичної критики.

Тут, на столі, перед вами лежить півсотні романів цього романодела. Вони є кращим доказом того, до чого може призвести невігластво письменника, наївність читача, а також мовчання критики, яка зазнає існування таких романістів».

Таким чином, ми маємо конфлікт між поняттями якість і популярність у літературі. Зрозуміло, що таким памфлетом неможливо було припинити видання бульварних романів. Але іронічний памфлет Шолом-Алейхема розплющив очі простому читачеві на запозиченість, чужорідність романів Шомера.

Друг Шолом-Алейхема Мордекай Спектор написав тоді: “Читачі захоплено прийняли “Суд над Шомером”. Багато хто з них соромився зізнатися, що колись читали Шомера. Книжки його рідко почали з’являтися на книжковому ринку”.

Шолом-Алейхем розумів причину критики (але не приймав її) його іншими виданнями, наприклад, «Фольксблат» і «Ха-мейліц», чиїм постійним автором він ще недавно був. Ці газети тепер звинувачували редактора “Єврейської народної бібліотеки” у підкупі єврейських письменників великими гонорарами. Причому ця критика подавалася в образливій формі, звинувачуючи Шолом-Алейхема в образі євреїв відсутністю в його творах успішних, розумних головних героїв; одні лише невдахи. Доходило навіть до звинувачень Шолом-Алейхема у юдофобстві (?!).

Ізраїль Леві, редактор газети «Фольксблат» писав: «Вже, дякувати Богу, більше 30 років минуло – а від наших великих просвітителів тільки й чути гостроти та насмішки над єврейськими звичаями, єврейським священнописанням та єврейським життям взагалі; вони сміються з живих і мертвих, вони висміюють усе, що дорого було євреям протягом тисячоліть. … У жодної нації, жодної мови немає такої диявольської літератури, як наша “нова література”, що складається з суцільного глузування, званого ними сатирою”.

Левинський з «Ха-мейліц» звинуватив Шолом-Алейхема в тому, що його “Єврейська народна бібліотека” “вбиває” єврейську літературу. Шолом-Алейхем не вважав за потрібне відповідати на такі випади. Проте, своєрідною відповіддю на це стала його повість на івриті “Шимеле” (опублікована в 1888 році у Варшаві в альманасі Нохума Соколова “Ха-асіф”) – історія доброї, але недолугої людини, яка живе в єврейському містечку. Шимеле – добра і чуйна людина, яка не здобула ні в кого доброго відношення. Надто вже Шимеле бешкетна, нестримна на мову, начитана світських книг інакомисляча людина.

З листа Шолом-Алейхема Дубнову можна дізнатися про те, що його турбувало в той момент:

“Ваш відкритий лист отримав. І рецензію Вашу у “Сході” читав. Ви – єдиний письменник, який співчутливо й гуманно ставиться до бідного жаргону (ідиш тоді вважався жаргоном). Важко висловити Вам ту щиру подяку, яку я мав висловити Вам. Я переживаю сьогодні стільки гонінь і несправедливих нападок на мене і на жаргон, з яким чомусь зв’язали моє ім’я, що не можу не радіти від будь-якого доброго слова. Особливо мені дістається від одного психопата, що забрав у свої нечисті руки єдиний “Народний листок”, який звернений їм тепер у клоаку для виливу помиїв на адресу жаргону та його адептів-шанувальників, особливо на мою адресу, після того як я – що б Ви думали? – Відмовив цьому пройдисвіту в позиці 6000 рублів! З того самого моменту і починається його похід проти мене та жаргону (нещасний, ні в чому не винний жаргон!). І Вам потрібно бачити, як видавець (він же фактичний редактор) жаргонної газети кричить у кожному номері: «Геть поганий жаргон!» Ось геройство! Але це нічого. Щоб остаточно підірвати авторитет жаргону, він у передових статтях, у фейлетонах, у політичній та іноземній хроніках оповідає читачам про те, що Шолом-Алейхем курить десятирублеві сигари і підкуповує своїх критиків (у тому числі і Вас, звичайно) для рекламування своїх творів і т.п. бруд, який повторювати соромно. І це все – у єдиному органі для маси! Дивно, як моя “Бібліотека” так швидко і з таким успіхом розійшлася в народі; а відгуки та співчуття людей щирих надають мені силу і бадьорість боротися проти явної несправедливості двома шляхами: зневажливим ставленням до будь-якої наволоти та енергійним прагненням уперед, поширюючи корисні книги у маси. Ваше зауваження щодо суттєвої прогалини в “Бібліотеці” – історичних популярних статей – прийняло до уваги душевну вдячність. Відданий Вам, Соломон Рабінович”.

Рафаель Літвін

© Times of Ukraine

. . . .

Sholem-Aleykhem (Sholom-Aleichem; March 3, 1859 – May 13, 1916)

The pen name of Sholem Rabinovitsh who was, according to his own designation “a humorist and writer,” he was born in Pereyaslav, Poltava. Together with Mendele Moykher-Sforim and Y. L. Perets, he laid the groundwork for modern Yiddish literature. He spent his youth in Voronko (in his writings, it was represented as Mazepevke-Kasrilevke) and Pereyaslav. His father Menakhem-Nokhum, both traditionally observant and a follower of the Jewish Enlightenment movement, gave him a good traditional education. After his mother’s death in 1872, he lived with his father’s family in Bohuslav. In 1873 he began teaching in a Russian school in Pereyaslav, which he ceased doing in 1876 with acclaim. While still a student, he made his first literary efforts (in Russian), and he wrote Der idisher robinzon kruzoe (The Jewish Robinson Crusoe). He found employment giving lessons in Russian in Pereyaslav and Rzhyshchiv. Over the years 1877-1879, he worked as a tutor in Sofiyivka, Kiev Province, to Hodl-Olga, daughter of a wealthy Jewish landowner, Elemeylekh Loyev, and she later became Sholem-Aleichem’s wife. He served as the state rabbi in Lubny, Poltava (1881-August 1883). He debuted in print with a Hebrew-language correspondence piece from Pereyaslav in Hatsfira (The siren) 6 (1879), defending the Pereyaslav Jews against earlier critical reports. In late 1881 and early 1882, he published in Hamelits (The advocate) his first articles, both concerned with Jewish education—“Haḥinukh veyeḥuso leavodat hatsava” (Education and the importance of military service) 51 (1881) and “Shealat hamelamdim” (The question posed by schoolteachers) 6 (1882). He wrote in Russian and sent pieces in to periodical publications, but the Russian editorial boards did not accept his writings for publication.

- Biography

1883-1892

“Tsvey shteyner” (Two stones), Sholem-Aleichem’s first story, was published in the summer of 1883 in installments in Aleksander Tsederboym’s St. Petersburg weekly Yudishes folksblat (Jewish people’s newspaper) (issues 26, 28, 30), and he signed it: “Sholem Rab-vitsh” and “Rabbi Sholem Rabinovitsh, Lubny, 1883.” It was dedicated to “O-L”—namely, Olga. The story was transparently autobiographical in the depiction of the romance of a young teacher with the daughter of a well-to-do merchant, although its conclusion is tragic. It appears to have been written shortly before Sholem-Aleichem’s marriage to Olga Loyev, which transpired on May 12, 1883 in Kiev, against the will of her father who soon came to terms with the young couple. At his father-in-law’s request, Sholem-Aleichem left his rabbinical post. From November 1883, he was living in Belotserkov (Bila Tserkva), where for a short time he held a job with the Brodsky family. After the death of his father-in-law in 1885, he gained control of his bequest and on his own went into business in Kiev, where he settled in September 1887. They lived there until October 1890, when with the failure of his business ventures, he went bankrupt and began wandering to Odessa, Paris, Vienna, Czernowitz, again Odessa, and Postav (Pastavy). He returned to Kiev in 1893 after his mother-in-law paid off his debts. The years 1883-1890 were among the most productive and versatile periods in Sholem-Aleichem’s creative life. In this formative period, he focused his efforts on Yiddish, moving in a series of directions and genres: in critical feuilletons, dramatic scenes, poetry, novels, and literary criticism. He also wrote in Hebrew and Russian and was active in the “Ḥoveve-tsiyon” (Lovers of Zion) movement. Until 1889 he writings were published in St. Petersburg’s Yudishes folksblat, and there he published his piece “Di vibores” (The election) (issue 38, 1883), which he signed for the first time “Sholem Aleykhem.” “Di vibores” is a pungent pseudo-correspondence piece from “Finsternish” (lit., darkness), consistently used in the satirical tradition of Jewish Enlightenment social criticism, a tendency that was evident in a series of other works by Sholem-Aleichem in this period. In these years, he also published in Moyshe-Leyb Lilienblum’s Der yudisher vekker (The Jewish alarm) (1887) and Der hoyz-fraynd (The house friend) (1888). Aside from the periodicals, he also published his writings in books and pamphlets, mainly in St. Petersburg, such as in Baylages tsum yudishes folksblat (Supplements to the Jewish people’s newspaper): “Natasha” (Natasha), later called “Taybele” (Taybele [lit., little dove]), (1884); “Hekher un nideriger” (Higher and lower) (1884); “Di velt-rayze” (The journey around the world), later called “Der ershter aroysfohr” (The maiden voyage) (1886-1887); “Leg-boymer” (Lag B’omer) (1887); “A khosn, a doktor!” (A bridegroom, a doctor!) (1887); “Kinder shpiel” (Children’s play) (1887); “Dos meserl” (The pocket knife) (1887); and “R’ sender blank” (Reb Sender Blank) (1888). In his father memory, he published A bintel blumen oder poezye ohn gramen (A bouquet of flowers, or poetry without rhymes) (Berdichev, 1888), 45 pp., later dubbed Blumen (Flowers). That same year in Berdichev, he published his pamphlet Shomers mishpet (The trial of Shomer [pseud. Nokhum-Meyer Shaykevitsh]), 103 pp. His campaigning Zionist story, Af yishev erets yisroel (In the settlement in the land of Israel), was published in Kiev in 1890 (44 pp.), later called Zelik mekhanik (Zelik the mechanic).

When “Dos meserl” appeared in print, Sholem-Aleichem for the first time had the honor of a completely favorable response from a Russian Jewish periodical, Shimen Dubnov in Voskhod (Arise). The warm reception strengthened his self-confidence in the writer-artist vocation. He went on (1888-1889) to publish and edit the immense collection Di yidishe folks-biblyothek (The Jewish people’s library), among the most important phenomena in Yiddish literature in this period of time. Sholem-Aleichem proved capable of attracting a string of writers, among them some who had at the time written only in Hebrew. It was in this collection that Y. L. Perets debuted in print in Yiddish with his poem “Monish” (Monish) and Mendele renewed his writing in Yiddish with an enlarged version of Dos vintshfingerl (The wishing ring). In addition to working under an assortment of pseudonyms, Sholem-Aleichem also published in his own name his two “Yiddish novels”: Stempenyu (Stempenyu) (vol. 1, 1888) and Yosele solovey (Yosele Solovey) (vol. 2, 1889). The collection aroused a sharp polemic in the Hebrew and Russian Jewish periodicals concerning the role of Yiddish and Yiddish literature in the Jewish community. The polemic and the collection itself had a major principled and lasting impact in strengthening the standing of Yiddish. Following his bankruptcy of 1890, Sholem-Aleichem was forced to discontinue publishing Di yidishe folks-biblyothek. In 1892 he tried to revive it with Kol mevaser tsu der yudisher folks-biblyothek (Herald to the Jewish people’s library) in Odessa, which he filled mostly with his own work under a variety of names. Here he published London (London), the first series of letters between Menakhem-Mendl and Sheyne-Sheyndl. He attempted again (1891-1892) to write in Russian, mainly for Odessa newspapers, and he also wrote in Hebrew. Together with Shiye-Khone Rabnitski, he published in Hamelits feuilleton-style book reviews, “Kevurat soferim” (Burial of writers), which they signed with the joint pen name: Eldad (Sholem-Aleichem) and Medad (Rabnitski).

1893-1898

When Sholem-Aleichem settled once again in 1893 in Kiev, he had to take a job in business and brokerage. With the discontinuation of Di yudishes folkblat in 1890, and until the founding of the weekly newspaper Der yud (The Jew) in Cracow in 1899, which was designation for Yiddish readers in the Russian empire, there was no regular Yiddish periodical publication in Eastern Europe, in which he could regularly publish his writings. In his sincere worries about making a living and with the shortage of eligible outlets in Yiddish, one can see the basic reasons for the period of relatively lesser productivity in Sholem-Aleichem’s work over the years 1893-1898. He nonetheless continued his literary activity and created work of enduring value. In 1894 in Der hoyz-fraynd (issue 4), for the first time he published a letter by Tevye the milkman and a monologue (later, Katonti [I am unworthy] and Dos groyse gevins [The big jackpot]). That same year, several of his stories appeared in American newspapers for the first time—Der toyb (The dove) in Pittsburgh and Filadelfyer shtodt tsaytung (Philadelphia city newspaper). At the same time, in Kiev in a special book publication, his first drama in full form appeared in print: the “comedy” Yaknehoz, oder der groyse berzenshpil (Yaknehoz, or the big gamble on the stock market)—and in it was his hero Menakhem-Mendl. Due to a denunciation by Kiev Jews, who recognized themselves in the figures portrayed, this book was confiscated. In 1896 he again published letters between Menakhem-Mendl and Sheyne-Sheyndl in the series “Papirlekh” (Slips of paper [Stocks and bonds]) in Der hoyz-fraynd (issue 5). In the period 1897-1898, Sholem-Aleichem was consumed with Zionist campaigning activity, which found expression in the pamphlets: Af vos bedarfen yuden a land? Etlikhe erenste verter farn folk (Why do Jews need a country? A few serious words for the people) (Warsaw: Shuldberg, 1898), 20 pp.; Meshiekhs tsayten, a tsienistishe roman (Messianic times, a Zionist novel) (Berdichev, 1898), unfinished; Tsu unzere shvester in tsien, etlikhe verter far yudishe tekhter (To our sister in Zion, a few words for Jewish daughters) (Warsaw: Shuldberg, 1898), 22 pp.; and Der yudisher kongres in bazel, etlekhe erenste verter farn folk (The Jewish congress in Basel, a few serious words for the people) (Warsaw: Shuldberg, 1898), 20 pp., which was Sholem-Aleichem’s adaptation in Yiddish of Max Mandelshtam’s speech at Kiev synagogues.

1899-1905

The rapid development of the Yiddish press and Yiddish periodicals in Eastern Europe, following the emergence of Der yud, had a particularly great and probably decisive influence on the intensity and colorfulness of Sholem-Aleichem’s writings from 1899 and thereafter. He published a great deal in Der yud until June 1902, contributed to Mortkhe Spektor’s Yudishe folks-tsaytung (Jewish people’s newspaper) and Di froyenvelt (The world of women) (1902-1903), and was principally a regular contributor to the first Yiddish daily newspaper in Russian Der fraynd (The friend) (from 1902) and later Der tog (The day) (1904-1905). Over the years 1899-1905, Sholem-Aleichem continued his Menakhem-Mendl series and the Tevye monologues. He published an entire series of his best stories, devoted further energies to drama (Tsezeyt un tseshpreyt [Scattered widely], 1903) and fiction (Moshkele ganef [Moshkele the thief], 1903), wrote journalism and criticism, and from time to time also published in Hebrew and Russian. Almost all of his works from these years were published for the first time in the aforementioned newspapers and journals—among the few exceptions: “A mayse on an ek” (A story without end), later called “Der farkishefter shnayder” (The enchanted tailor), appeared in a separate booklet in Warsaw (1901). Thanks to the regular contributions to the widespread press, Sholem-Aleichem’s popularity grew, as did the affection of his Jewish readers. It was in these years, 1899-1905, that writing became his principal mode of employment.

In 1903 a four-volume collection of Sholem-Aleichem’s Yiddish writings was published in Warsaw, and from 1905 dozens of his writings were published in Magnus Krinski’s “Bikher far ale” (Books for all) series in Warsaw, works which had generally appeared previously in newspapers. In April 1905 a Polish theater staged to great success his play Tsezeyt un tseshpreyt—the first time that a play by Sholem-Aleichem was performed by a professional theater company. In 1905 he read his works before large Jewish audiences in a string of cities in the Baltic states and Poland. In these same years, he continued his Zionist activities with speeches (1899, with Mark Varshavski), and he published Zionist journalistic pieces (“A refue shleyme” [A full recovery], 1902; “Umzistik broyt” [Free bread], 1904); in a separate pamphlet: Doktor teodor hertsl, zayn leben, zayn arbayten farn yudishen folk un zayn frihtsaytiger toydt [Dr. Theodor Herzl, his life, his work for the Jewish people, and his premature death], Odessa, 1904, 45 pp.). In 1904 he made unsuccessful attempts to publish a Yiddish daily newspaper in Odessa or Vilna, and in 1905 he also tried to establish a Yiddish art theater in Odessa, where he would have been the leading literary figure.

He was active in 1903 in preparing and publishing the anthology Hilf (Relief) on behalf of the victims of the Kishinev pogrom. He translated from Russian into Yiddish three stories by Leo Tolstoy, which he received from the author for the anthology. In 1904 he became acquainted with a number of Russian authors, such as Maxim Gorky, Leonid Andreev, and Aleksandr Kuprin, and in Vilna with the young Yitskhok-Dov Berkovitsh who in that very year would become his son-in-law. Berkovitsh would also become his translator from Yiddish into Hebrew, worked closely with his father-in-law until Sholem-Aleichem’s death, and attended to editions of his work and his immense archive, which he began to assemble while Sholem-Aleichem was still living.

1905-1916

After the harsh experiences of the Kiev pogrom in October 1905, Sholem-Aleichem and his family left the Russian empire. Not counting his two trips back, in 1908 and 1914, he in fact left Eastern Europe for good, and thus there began for him an era of often painful wandering which continued until December 1914. On his way from Kiev to the United States in 1905, he spent time in Brod, lived in Lemberg, and from there traveled through Galicia, reading his works before audiences; he was in Bukovina, Vienna, Romania, Switzerland, Belgium, and Paris, stopped for a time in Geneva and London, and arrived in New York in October 1906. Here he tried to find a place for himself as an author and playwright, but he suffered a series of failures and in the summer of 1907 returned to Geneva, where he lived until May 1908. That same summer, during his successful tour of public readings in Poland and Russia, he became seriously ill with a lung ailment in Baranovitsh (Baranovichi). From that point, he was confined to his bed for a lengthy period of time, had to undergo continual treatment, and watch his health under proper climatic conditions. Thus, from 1908 to 1914, he lived in Italy, Switzerland, and Germany, on several occasions in sanatoriums and spas. With the outbreak of WWI, he left Berlin with great difficulty, traveled through neutral Denmark, and reached New York.

Aside from the unfavorable circumstances of his years of wandering and constant sickly condition from 1908, Sholem-Aleichem continued writing in the era from 1905 until his death in an utterly intensive manner. This difficult period was also the most mature in his work. In addition to dozens of feuilletons and extraordinary stories, from 1907 he wrote one of his crowning works: Motl peysi dem khazns (Motl the son of Peysi the cantor). He also wrote more monologues; the novels Der mabl (The deluge) (1907, later known as In shturem [In the storm]), Blondzhende shtern (Wandering stars) (1909-1910), Der blutiger shpas (The bloody hoax) (1912), and Der misteyk (The mistake) (1915); he returned Menakhem-Mendl from America to Poland and prepared the second volume of Menakhem-Mendl’s letters (1913); he revised his earlier writings for the theater, Yaknehoz retitled as Der oysvurf oder shmuel pasternak (The scoundrel or Shmuel Pasternak) (1907), Stempenyu as Yudishe tekhter (Jewish daughters) (1907), and Der blutiger shpas as Shver tsu zayn a yid (Hard to be a Jew); he dramatized Tevye der milkhiger (Tevye the milkman) (1914); and he wrote two new plays, Der oytser (The treasure) (1907 or 1908) and Dos groyse gevins (1915). In the last year of his life, he published his immense, unfinished autobiography, Funem yarid (From the fair), and continued Motl peysi dem khazns in the United States.

Virtually all of Sholem-Aleichem’s work in the years 1905-1916 first appeared in newspapers and magazines. Until WWI he continued contributing to Eastern European periodicals. And, although separated physically from Eastern Europe, he responded immediately to almost every actual event in Jewish life and wrote about it in the dailies Der fraynd and later Dos leben (The life) (1914); he also published in Di tsayt (The times) in Vilna (1906), Unzer leben (Our life) in Warsaw (1910-1911), Kiever vort (Kiev word) (1910), Gut-morgen (Good morning) in Odessa (1911), and Lodzer tageblat (Lodz daily newspaper) (1914). His work may also be found in such journals as: Dos yudishe folk (The Jewish people) in Vilna (1906-1908), Der shtrahl (The beam [of light]) in Warsaw (1910), Fraye teg (Free days) in Warsaw (1910), Bobroysker vokhenblat (Babruysk weekly newspaper) (1912), Der zhurnalist (The journalist) in Warsaw (1911), and Di yudishe velt (The Jewish world) in Vilna (1914).

After being a wanderer throughout Galicia, Sholem-Aleichem published in New York’s Yidishes tageblat (Jewish daily newspaper) his Pogrom-bilder (Pogrom scenes). However, his regular contributions to the Yiddish press in New York had begun with his visit to America in 1907. From that point in time, he also frequently published his writings both in the Eastern European periodical press and in New York (on several occasions under various titles). In Varhayt (Truth) he published in 1901 and later in 1906, in Yidishes tageblat until 1914 with interruptions, in Morgn-zhurnal (Morning journal) over the years 1909-1911, and in 1915 he became linked to Tog. He also placed work in: Der amerikaner (The American) (1907-1913) and Der groyser kundes (The great prankster) (1910-1912, 1916). During his wanderings, he also wrote pieces for: Lemberger tageblat (Lemberg daily newspaper) (1906), Tshernovitser vokhenblat (Czernowitz weekly newspaper) (1906), Zhurnal (Journal) and Ekspres (Express) in London (1906), and Der nayer zhurnal (The new journal) in Paris (1914).

On October 25, 1908, the entire Yiddish world celebrated the twenty-fifth anniversary of Sholem-Aleichem’s creative work in Yiddish. The receipts were used for the ailing writer and a portion to buy up from Warsaw publishers the rights to his writings, and in 1909 a multi-volume jubilee edition of Sholem-Aleichem’s writings began to appear in print. For this edition, he assembled and revised into book form the Menakhem-Mendl series and unified into book form Tevye’s monologues and the first part of Motl peysi dem khazns. With the outbreak of WWI, the publication was cut short midway. This would be the last edition of his writings that would appear in his lifetime. From the earlier edition of his writings (1903) and from the jubilee edition, there was published in Warsaw in the series “Familyen-biblyotek” (Family library) several dozen separate booklets of Sholem-Aleichem’s stories and chapters of his longer works. Over the course of the years 1909-1915, they were bought up by the hundreds of thousands of copies. The great success of the jubilee edition and of his writings in “Familyen-biblyotek” until WWI established for the author a secure and regular living. A truly great success was enjoyed by the three-volume edition of his works, translated into Hebrew by Y. D. Berkovitsh (on occasion with the help of the author). These were published by the Warsaw publishing house of “Hashaḥar” (The dawn) (1911?-1913). Over the period 1910-1913 there was published in Moscow an eight-volume, authorized edition of his writings in Y. Pinus’s Russian translation; Hannah Berman’s English translation of Stempenyu (London: Methuen, 1913), 303 pp.; a collection of stories in Nathan Birnbaum’s German translation (Berlin: Jüdischer verlag, 1914), 140 pp. Sholem-Aleichem’s writings began to become known by non-Jewish readers as well.

In his last years, he remained active in the Zionist movement. He took part in 1907 in the Zionist congress in The Hague as a New York delegate. That same year he published in New York’s Yidishes tageblat his impressions of the congress under the title “Kongres-bilder” (Congress scenes). In 1907 he became acquainted with Ḥaim Naḥman Bialik in Geneva, where both writers spent time with Mendele and Ben-Ami, a meeting that was immortalized in Sholem-Aleichem’s “Fir zenen mir gezesn” (The four of us sitting).

He arrived in New York in late 1914, physically exhausted, suffering from disappointments, and after news of the death of his son Misha in the late summer of 1915, grieving constantly. On Iyar 10 (May 13), 1916, after a long period of suffering, he died. Two days later his funeral took place in New York with 100,000 in attendance.

Criticism and Research

From Shimon Dubnov’s favorable response to Dos meserl, the unfavorable reviews by Yoysef-Yude Lerner (of Sender blank and A bintel blumen, both in 1888) and by Yude-Leyb Gordon (of Kinder shpiel, 1889) in Yudishes folksblat, and until nowadays, Sholem-Aleichem criticism and research consists of thousands of items in Yiddish, Hebrew, Russian, English, and other languages. We lack, however, a complete bibliographic listing of these works. Aside from several summations, we still lack a detailed examination of criticism and research works on Sholem-Aleichem and their history. It would appear that such work is a faithful reflection of the critical attitudes, ideologies, and research methods that have accompanied Yiddish literature from the 1880s till today. For many years during Sholem-Aleichem’s life, a number of critics held that his works were “dated” and that they mainly consist of pleasant entertainment, without artistic value or any implications. Sholem-Aleichem himself had not experienced the modernist contemporary tendencies in literature and oftentimes came out publicly against them. The feeling was mutual, and between the modernists and the renewers in Yiddish literature at the start of the century, Sholem-Aleichem’s writings were often covered in defamation. Shmuel Niger, later one of the most important critics and researchers into Sholem-Aleichem’s writings, admitted to a “sin” of this sort in an article of his from 1908. And, he was not in those years the only one to later change his opinion. It appears that the publication of Sholem-Aleichem’s work in the multi-volume editions of 1909-1915 and after his death the “Folksfond” editions of his writings had an enormous impact on the gradual transformation of attitudes toward him.

Critics and researchers covering the range of social ideologies frequently accused Sholem-Aleichem of a petit-bourgeois inclination and sometimes were unable to deal with his nationalist Zionist tendencies. In the 1920s, people in the Soviet Union were still writing about his works in such a spirit and even much later were censuring his writings, if they failed to fit with contemporary obligatory attitudes. Some critics who grasped Sholem-Aleichem’s immense talent never went beyond the realm of impressions. They were sometimes more an expression of intuitive enthusiasm for the great writer than they were a contribution to the critical challenge posed by the phenomenon of Sholem-Aleichem in our literature. One nevertheless often finds in such impressionistic criticism as well truly fine and sensible observations. There is also in Sholem-Aleichem criticism a tendency toward crafty metaphorical reading into his work which on occasion contradicts the writer’s primary intensiveness. The more disciplined Sholem-Aleichem researchers reflect as well the historical development of research methodologies, modes, and ideologies. They are, however, concerned with noting a string of enduring accomplishments. Great achievements have been made by Soviet Yiddish research on Sholem-Aleichem (Nokhum Oyslender, Meyer Viner, Maks Erik, Yekhezkl Dobrushin, Elye Spivak, and others). Shmuel Niger’s book is, until now, the most comprehensive monograph on Sholem-Aleichem’s writings, and Zalmen Zilbertsvayg’s work on his plays and their realization in the theater—in his Leksikon fun yidishn teater (Handbook of the Yiddish theater)—is extremely useful. In recent years a multiplicity of detailed studies of Sholem-Aleichem’s works have been produced, but we still lack for a general, detailed monograph on his life and work as well as a series of reliable research pieces on particular aspects of his work.[1] So that such expectations might be able to be fulfilled, we need a full bibliography of Sholem-Aleichem’s writings and mainly a textologically trustworthy edition of all his writings in Yiddish, Hebrew, and Russian.

- Menakhem-mendl, Tevye der milkhiker, and Motl peysi dem khazns

Sholem-Aleichem’s literary heritage is extraordinarily rich and many-sided. It includes all the established literary-artistic and journalistic genres. Readers, critics, and researchers of his work, though, point out three masterful works—Menakhem-mendl, Tevye der milkhiker, and Motl peysi dem khazns—which are not easily placed according to accepted definitions of genres. These three works were written over the course of years in separate series and were later published in book form: Menakhem-mendl (1892-1913), Tevye (1894-1914), and Motl (1907-1916). In all three works, Sholem-Aleichem used a variety of forms of direct speech: Menakhem-mendl consists of letters among him, his wife Sheyne-Sheyndl, and Sholem-Aleichem; Tevye consists of one letter to Sholem-Aleichem and of separate monologues “belonging” to Sholem-Aleichem; and Motl describes his biographical adventures also in direct speech, but not in a sufficiently clear situation. Every figure is formed by that character’s own specific language with distinctive features of style that are an essential component of the personality, his character, and his fate.

Sheyne-Sheyndl’s letters reflect the small-town limited and sometimes coarse world of ideas, but soaked through with large, empty, hereditary folk wisdom; the penetration of the big city in Yiddish is fixed in Menakhem-Mendl’s language, his speech contrasted with the possibilities of Sheyne-Sheyndl’s expressions and conceptions, although the language of both conforms to the traditional letter style. Thanks to the completely unreal fiction that Menakhem-Mendl would never return to his family in Kasrilevke, Sholem-Aleichem created the possibility of an open and at first glance limitless number of situations and possible temptations, with which his hero will attempt in the vehement chase of the “luftmentsh” [someone with no clear means of support] who will relentlessly be caught in the course of Jewish history in Eastern Europe of the late nineteenth century and early twentieth. The small-town individual would try to find his place at the time in the big city and find there new chimerical joys. Around 1910 Sholem-Aleichem reworked into book form a portion of the series of letters published earlier as a “second edition” and evened out the contradictions, eliminated a number of obscenities in Sheyne-Sheyndl’s letters, and snuffed out the earlier feuilletonist, contemporary character of the newspaper style. In 1913 he returned to his beloved figure in the “second tome” of Menakhem-Mendl’s letters, in which, having returned from America, the hero becomes a contributor to a Warsaw Yiddish newspaper. The new series carries a very strong feuilleton character which may impede the contemporary reader from seeing the genius of this continuation.

Tevye’s language and style are a finer synthesis of the simple speech of a toiling Jew with an ostensibly scholarly overlay which is broadly made manifest in the frequent citation of verses and commentaries in Hebrew or Aramaic. The circuit of his citations, though, is highly circumscribed, from Torah with the readings from the Prophets, from the prayers, and from Psalms. In the main, however, Tevye’s textual references appear sometimes with multiple and sometimes with sly “incorrect” meanings and explanations. This distinctive style also reflects the ideal of erudition which predominates in all realms of traditional Jewish society. Initially conceived as the antithesis of Menakhem-Mendl the “luftmentsh,” Tevye stands with both feet on the ground, full of vital, physical strength and healthy, mental senses. Over the years the series changed into a chain of romantic conflicts, in which Tevye’s daughters entangled their father with their “modern” ideas of love which collided with the well-established tradition of matchmakers. New winds disrupt the traditional concepts and pose before Tevye a stark confrontation with new sensibilities, problems, and solutions. Also, here, the contemporary background to situations are apparent.

Motl peysi dem khazns which, at the time of its first publication, was dubbed “a plotline about the son of a cantor,” and later as “the travel descriptions of a seven-year-old orphan on his way…to America,” is a magnificent pseudo-autobiographical fiction of contrasts in language and meaning between the seven-year-old storyteller and his adult surroundings. As a stable motif in the book, these contrasts belong among the subtlest accomplishments of Sholem-Aleichem’s creative work in his searching for a direct feel and tenor of the language coinages which in the mouth of adults lose their true significance. The infiltration of new, foreign language elements in Kasrilevke Yiddish provides a further basis for the distinctive stylistic shaping that reflects new language contacts of the small-town gang of folks on their way to America and in America. The three portions of the book—in the old country, en route to America, and in the United States—were a further reflection of the actual, shaken world of the great Jewish emigration from Eastern Europe on the eve of WWI. And, because this is presented through the prism of ostensibly artless and happy childish experiences, the book rises to a higher artistic achievement in the challenge of Yiddish literature to deal with the theme of emigration. Because of their necessarily tight linkage to the Jewish way of life, to Yiddish language habits, and to the Jewish fate at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries, the three figures become universal in their elementary human world view.

Stories

The short story belongs among Sholem-Aleichem’s highest artistic achievements. And, a truly prominent place in his storytelling heritage is occupied by stories for children. The stories in the two-volume Mayses far yidishe kinder (Stories for Jewish children) and in Berkovitsh’s Hebrew translation in Sipure maasiyot leyalde yisroel (Stories for Jewish children) belong, together with Motl peysi dem khazns, among the classics of children’s literature for Jews. In their themes and their forms, Sholem-Aleichem’s stories are for both children and adults multicolored and diverse. Should we single out a series of thematically constant elements, such as the attachment to the annual cycle of Jewish holidays (clearly represented in his children’s stories), the descriptive definitiveness of place and time (old-new Kasrilevke), and the direct responses to actual events and trials in Jewish life in the writer’s era. There is a tendency to connect specific stories to series and cycles according to place (Kasrilevke) and situations (railway stories, starting with the subheading “A pekl” [A bundle]). Also in his short stories, there is a wealth of “I”-format in the most diverse of variations and among them the monologue.

Sholem-Aleichem’s own genre designations were not overly fastidious, and they do not reflect the rich colorfulness of possibilities. The label “mayse” (story) dominated for him various additional declarations, such as “for Jewish children,” “a story such as…,” “a true…,” “extraordinary,” “fantastic,” “wonderful,” “heartrending,” “joyous,” etc. He also used for his stories such designations as “description,” “history,” “scene,” “characters,” “episodes,” and also “novel,” “dialogue,” “tragedy,” “poem,” “song,” and the like. The range of his storytelling art was broad indeed. We find in his work the allegorical and symbolic story, the masterfully developing anecdote, memoirs and quasi-memoirs, grotesque fantasy and the absurd matched by him in a natural manner with the descriptive accuracy of “real” detail, jokes with seriousness, lyricism with biting satire. Often this is not a “pure” revelation, and several elements are intertwined in one short story. Like the majority of Sholem-Aleichem’s other work, just as when they are tragically subtle, his humor is a dominant foundation, and it appears in the most diverse of forms: comical situations, descriptions of physical idiosyncrasies, bizarre gestures of his figures, and mainly: linguistic humor in all its possible forms. The principal basis of Sholem-Aleichem’s storytelling art, together with his immense skill in the construction of the story, determined its success for young and old.

Novels

There is considerable evidence that Sholem-Aleichem devoted a great deal of his writer’s energy to the challenge of the novel, and in the novel he sought to see his highest artistic and literary achievement. Concerning the novel, and more specifically the “Yiddish novel,” in the late 1880s he developed his most important critical and theoretical statements. The challenge of the novel began for him even before he arrived at Yiddish. We know from his Funem yarid that, while he was in Sofiyivka in the late 1870s, he “wrote…all night long—great, heartrending novels,” all of them apparently in Russian. “Tsvey shteyner” centers around such a “heartrending” fictional conflict. His first effort at a more full-fledged novel was the “story” “Natasha,” “Kinder shpiel” (1885-1886?), and “Di velt-rayze” (1886-1887, later titled “Der ershter aroysfohr”). In “Natasha” and “Kinder shpiel,” the foundations of the sentimental novel and the direct influence of the contemporary Russian novel are entire visible. In each of his early efforts, Sholem-Aleichem still wrestled with the traditions of the Jewish Enlightenment. The beginnings of the challenge with the “Yiddish novel” are readily apparent in R’ sender blank un zayn filgeshetste familye (Reb Sender Blank and his highly esteemed family) (1888). The subtitle, “A roman ohn a liebe” (A novel without love), was meant to mark it off from sentimental, romantic material for a planned family trilogy, of which we ultimately only received the first part. Around 1888 Sholem-Aleichem intensified his fight against the trashy Yiddish novel (Shomers mishpet, 1888) and came forward with his suggestions regarding the “Yiddish novel,” the main point of which was the demand that they faithfully reflect Jewish reality and the specifically Jewish conflicts in the novel and the resolutions contrary to the novel which conveys into Yiddish alien examples, heroes, and sensational subject matter. Searching for appropriate protagonists for the “Yiddish novel,” Sholem-Aleichem concentrated in this period on his artistic figures of Stempenyu (1888) and Yosele solovey (1889), finding in the musical fiddler and cantorial singer the fitting heroes for possible Jewish love conflicts. Moshkele ganef (1903; in manuscript entitled Blut un trern [Blood and tears], and in its serialized version in Varhayt [Truth] from 1918 as In yene teg [In those days]) belongs, according to Sholem-Aleichem’s letters to Mortkhe Spektor, to his “Yiddish novels” written “à la Stempanyu.” At the center stands the daughter of a religious Jewish family, as in earlier “Yiddish novels”; she has fallen in love with a non-Jew, and at the very last moment she is saved from conversion to Christianity by a beloved, Jewish, “sympathetic” thief. As is the case with Stempenyu and Yosele Solovey and later the characters in Blondzhende shtern, so too is Moshkele a “real” Jewish love hero who belongs to the margins of or is detached from established Jewish society, because only in those environs did Sholem-Aleichem find figures with contradictions who could warrant sharp or “real” love conflicts throughout Jewish surroundings. The unfinished “novel” Meshiekhs tsayten (1898) belongs more closely to Sholem-Aleichem’s Zionist campaigning work than it does to the novel form. The unfinished novel Ver veyst? (Who knows?) and Mayne ershter roman (My first novel) (1903) were more well-developed anecdotes than novels. In Der mabl (serialized in Unzer leben, 1907), the era of the 1905 Revolution and the pogroms is foregrounded, introducing into the novel the figures of the modern Jewish intellectual and his role in national political aspirations. In Blondzhende shtern (1909-1910, serialized in Warsaw’s Haynt [Today] and New York’s Morgn-zhurnal, and later revised), Sholem-Aleichem presented a broadly conceived picture of the Yiddish theater and art world with a series of unforgettable figures. The novel should be considered a continuation of earlier artistic novels. Its core may be found in Sholem-Aleichem’s Hebrew story “Simla” (1889) dating to the era of Stempenyu and Yosele solovey. A number of critics consider Blondzhende shtern, in its later revised version, to be Sholem-Aleichem’s best novel, which to this day remains a great success among his Russian readers. Der blutiger shpas (serialized in Haynt, 1912-1913)—an actual response to the condition of Jews in the Russian empire in the era of the Beilis Trial—was a novel with clear traces in the pressing work of providing “interesting” material for the daily press. Sholem-Aleichem also partially revised this novel for publication in book form. Der misteyk (installments in Tog in New York, 1915) is “a novel with a moral which takes place in America.” This was Sholem-Aleichem’s last, unfinished, and not terribly successful effort to handle in the novel form the Jewish emigrant surroundings in the new world. Only a small part of the novel, full of Americanisms, remains extant. Also amply evident in his novels was Sholem-Aleichem’s masterful use of humor in all its possible manifestations: his figures are poignantly and often presented very flexibly; there is in some of them journalistic and literary critical digressions; also in his novel one finds his extraordinary artistic talent in writing direct speech, although rendered through an omniscient, concealed storyteller. The majority of critics argue that, only in his three artistic novels, did Sholem-Aleichem reach the culmination point of his challenge with the novel form.

Drama

Drama, theater, and later film were an intrinsic component of Sholem-Aleichem’s creative work. His profound interest in Yiddish theater was manifested from his Hebrew-language “Simla” through Blondzhende shtern. One should also consider his monologues, dialogues, and scenes—broadly represented by his own designations, and in fact in a more prominent place in the storytelling genre—as branches of drama and theater in his writings, because they occupy till this day a prominent position in presentations of Sholem-Aleichem’s work for the stage via specialist public readers, in addition to Sholem-Aleichem himself who did this to great success. He would also frequently use the dramatic form for feuilletons, sometimes as pure publicity which actually had little to do with drama or theater (for example, in Kultura [Culture], 1900). Several of his first short efforts in dramatic form, such as A khosn a doktor! (1887) (dubbed a “Shtub-zakh” [Household affair]) and “Di asife” (The assembly) (1889), described as “pure comedy,” Sholem-Aleichem himself marked as feuilletons. In their revised form of 1905, A khosn a doktor! and Der get (The divorce) (originally, 1888) gained improvement in staged forms. Yaknehoz was Sholem-Aleichem’s first major dramatic challenge. In its first version, Yaknehoz was much closer to spoken drama. It is highly doubtful if Sholem-Aleichem, because of the ban on Yiddish theater in the Russian empire, was able to conceive in the 1890s of comedy for the stage which was also received by the “victims” in Kiev as a completely faithful, although humorous and satirical, reflection of the people working on the Kiev stock exchange. A much closer theme “for one of the awakened heroes of Yehupets” is dealt with as comedy in his one-act play Mazl tov! (Congratulations!) of 1899 (later entitled Farbitn di yoytsres [Things all confused]).

Sholem-Aleichem’s first dramatic effort to achieve great success was his Tsezeyt un tseshpreyt, bilder funem yudishen leben (Widely scattered, scenes from Jewish life) (revised anew in 1906). Sholem-Aleichem also introduced here a small-town parvenu protagonist with his family in the big city and the rupture between the old-fashioned, small-town parents and their children who are already somewhat enchanted by modern political-ideological activity and empty, big-city enjoyments. From 1905, when the ban on Yiddish theater in the Russian empire was lifted, and later in connection with Sholem-Aleichem’s hopes for performances in the American Yiddish theater, his broadened and deepened interest in drama and theater became more apparent. From these years more stage-worthy reworkings of his earlier plays derive; he also composed at this time his new one-act plays, Agenten (Agents) (1905) and Menshen (People) (1907); and he launched a number of dramatic attempts with which he alone was unhappy, did not published, and even burned some of them: Der letster korbn (The last victim) (1905, on the pogroms and the revolution), Dovid ben dovid (David, son of David) (1906), Dos naye lebn (The new life) (1907), and Vuhin? (To where?) (1907). The dramatization of his novel Stempenyu dates to 1905; it was staged in New York but never published. And, it would appear that in his own dramatizations of his works, Sholem-Aleichem found his way to drama and to theater. Both of his plays Tevye der milkhiker (in its present form, apparently dating to early 1914) and Shver tsu zayn a yid (1914), based on his novel Der blutiger shpas, for many years would remain part of the standard repertoire of the Yiddish theater. In later years Tevye came back to life in Fiddler on the Roof in theaters around the entire world and in film.

Sholem-Aleichem’s best two comedies were written in the last years of his life. Dos groyse gevins oder 200,000 (The big jackpot, or 200,000) (1915) had phenomenal success in an array of staging in the Yiddish and in the Hebrew theater. Der oytser (which he began writing in 1907 and was published posthumously as Di goldgreber [The gold diggers]) was thought by some critics to be Sholem-Aleichem’s best play. In those years, he also wrote the one-act plays: Kenig pik (King of spades) (1910), Shrage (Shrage) (1911), Oylem habe (The world to come) (1915), Mister boym in klazet (Mister Boym in the closet) (1915), and In tsveyen a zeks un zekhtsik (Two times sixty-six) (1916, which also existed in an earlier version). Some of his one-act plays were staged by professional theaters and were very successful. They, too, belong to the standing repertoire of amateur dramatic circles. A number of Sholem-Aleichem’s writings were dramatized by others, among them Blondzhende shtern. For his achievements and success in drama and theater, Sholem-Aleichem had his masterful wordsmith ability in forming the figures through direct speech, which was already well apparent at the beginning of his non-dramatic works. Together with the elements of humor, also evident in his plays, all of which acquired a specific character of the author’s creation. From 1905, however, one begins to note an altogether ascending skill as well in the staged form of his dramas and in their markedly theatrical construction. Sholem-Aleichem was the first Yiddish writer to display a direct interest in cinema. In 1913 he prepared scripts in Russian for filming Dos groyse gevins, for Khave (Eve) from the book Tevye der milkhiker, for Motl peysi dem khazns, for Stempenyu, and for Der farkishefter shnayder. Nothing, though, was to come of these movie projects. The scripts remain in manuscript. In Yiddish his Di velt geyt tsurik (The world is going backwards) (1913) is labelled in its subtitle “A sinema-fantazye lekoved khanike” (A cinematic fantasy in honor of Hanukkah) and was written directly as a film script. A full array of Sholem-Aleichem’s works were filmed, among them Menakhem-mendl (Soviet Union, 1925), on the basis of a script by Isaac Babel.

Poetic Efforts

In the first years of his writing in Yiddish, late 1883 and through 1884, Sholem-Aleichem also tried his hand at poetry. At that time he published thirteen poems in Yudishes folkblat. There was in these poems the descriptive groundwork with an Enlightenment-satirical, critical tendency together with expressions of national sentiment. Clearly here was the unmediated influence of Russian poetry, principally that of Nikolai Nekrasov to whom Sholem-Aleichem referred on several occasions. Yehuda-Leyb Gordon also exerted an influence on his poetry, and between them there was also Sholem-Aleichem’s Yiddish translation of Gordon’s “Aḥoti ruḥama” (My sister Ruhama). It also appears that Sholem-Aleichem looked around very quickly and saw that poetry was not his métier. When the publishers of Yudishes folkblat called upon him to submit more poetry, in the poem he sent them, “Efentlikher antvort” (Public reply) 47-48 (1887), he expressed his opposition to the improvisational poetry characteristic of wedding entertainers and declared: “I’m hardly a poet!” And, in the last stanza, he wrote openly: “It is much easier for me to write prose than it is to sing before a holiday.” Nevertheless, in 1887, 1889, and 1892, he published individual poems. Here and there in his prose, one finds a rhymed passage, and in 1892 he again in his Kol mevaser tsu der yudisher folks-biblyothek published his long, unfinished poem, “Progres tsivilizatsye” (Progress, civilization) (also appearing Tog in New York in 1924 under the title “In bes-hamedresh” [In the prayer house]). Sholem-Aleichem’s last poetic efforts would include his poem of political currency, “Shlof alekse” (Sleep, Alexey), of 1905 and his well-known epitaph written that same year [after the pogroms throughout the Russian empire]. Three of Sholem-Aleichem’s poems spread quickly from mouth to mouth: “Erev shabes” (Sabbath eve) (1883), “Shlof, mayn kind!” (Sleep, my child!) (1892), and “Shlof alekse.” He evinced great interest in Yiddish folksongs which he cites in an array of his works. He was close to the folk poet Mark Varshavski and twice wrote prefaces to Varshavski’s poetry collections (1901-1914).

Literary Criticism

In the first period of his creative work, Sholem’s-Aleichem’s role in contemporary literary criticism is amply apparent, both in a large number of digressions in his fictional writings and in a series of individual critical works. At that time, he considered criticism an important part of his literary work and through it sought to influence the development of all forms of literature among Jews. His first dedicated critical work was an 1887 review of Yoysef Petrikovski’s Russian volume, V ameriku (To America). His main critical articles, though, date to the years 1888-1889. In 1888 he published serially in Yudishes folksblat a lengthy overview of contemporary Yiddish literature: “Der yudisher dales in di beste verke fun unzere folks-shriftshteler” (Jewish poverty in the best works of our popular writers). In this piece, he dealt with Mendele’s Fishke der krumer (Fishke the lame), as well as writings by Avrom Goldfaden, Ayzik-Meyer Dik, Yitskhok-Yoyel Linetski, Mortkhe Spektor, and Moyshe-Arn Shatskes, introducing through them Jewish poverty as a principal theme in Yiddish literature. The promised continuation on Avrom-Ber Gotlober, Yankev Dinezon, Elyokem Tsunzer, and others was never published. In Yudishe folks-biblyotek (Jewish people’s library) (1888) and in Kol mevaser tsu der yudisher folks-biblyothek (1892), as well as in Hebrew with Shiye-Khone Rabnitski, he published a number of reviews of Yiddish and Hebrew books, often in a sharp, biting tone, but not always completely correct. His main critical feat for those years is doubtless his fight against Shomer and pursuant pieces in a string of digressive notes in his work, in Shomers mishpet (1888), and in his efforts to justify the realist “Yiddish novel.” In 1888 he also published “Hayne un berne un zeyere gedanken iber yuden” (Heine and Börne and their thoughts about Jews) and his survey “Di rusishe kritik vegn yudishn zhargon” (Russian criticism of Yiddish [lit. the Jewish jargon]). In subsequent years, he was a less frequent literary critic and carried on more often a feuilletonist, parodic character, as in “In sforim-kleytl (a shpas)” (In the bookshop, a joke), a more caustic satire of Shomer’s depraved taste among Yiddish readers (1889), “Az got vil, shist a bezem” (If God wills it, a broom can shoot) (1908, a kosher-for-Passover tragedy, written in a decadent-symbolic style), and “Komedye brok” (Comedy of Brok) (a new Purim play in two acts countering Y. Yushkevitsh’s Russian play, 1910). In his volume Yidishe shrayber (Yiddish writers) are assembled mainly memoirs concerning writers of his era, and many of them address Sholem-Aleichem’s attitude toward literary issues. There is still not extensive work on this attitude of his. For such a work, it will be necessary to take into consideration not only his specifically literary critical writings, but also a great number of digressions, passing footnotes and allusions scattered and spread in his fictional writings, and also everything that has been preserved in his epistolary bequest concerning literature. It does appear, however, to be generally correct that Sholem-Aleichem, while combatting cheap, trashy literature and other wildlife in our trilingual literature, had little understanding of modernist tendencies which were, at least since the beginning the twentieth century, permeating Yiddish literature as well. Every year there remained solely authoritative the achievement of “realistic” literature of the nineteenth century, especially in Russian.

Hebrew and Russian Writings, Translations

Relying on Shimon Dubnov’s statements, Sholem-Aleichem himself held that in principle contemporary Yiddish literature in Eastern Europe was linguistically speaking three-storied: Hebrew, Yiddish, and also Russian, if written by Jews for Jews. Admirably capable in both Hebrew and Russian and proficient in both literatures, Sholem-Aleichem in various periods tested his hand at both of these languages, although already in the 1880s it was, apparently, quite clear that his main, artistic language medium was Yiddish. Only in Yiddish, in the linguistic basis of Jewish reality upon which he built his work, was he able without the least limitation of the most varied sort, linguistic or stylistic, to arrive at a free and full expression of his distinctive talent. In addition to the aforementioned correspondence pieces and articles from the late 1870s and early 1880s, he wrote and published in Hebrew in two eras: 1888-1892 and 1901-1908. In the former were his Hebrew stories, all originals save one translated from Yiddish, and with no directly parallel texts in Yiddish, although they dealt with the same themes and in the same manner as his Yiddish writings of this period. In the latter were mainly his stories in his own translation or versions of his Yiddish stories. Sholem-Aleichem’s Hebrew works were compiled in Ketavim ivriyim (Hebrew writings), compiled and edited by Chone Shmeruk (Jerusalem: Mossad Bialik, 1976).

Sholem-Aleichem’s first Russian story, “Mechtateli” (The dreamers), was published in 1884. It appears that his main efforts in Russian fall at the beginning of the 1890s, although he also published several Russian stories in 1898 and 1899, and in 1913 the scripts, noted above, for films in Russian. Some of these, from the early 1890s, were published in the Odessa press, and have apparently remained unknown even by researchers of his writings. The Russian stories known to us were also composed on Jewish themes, and the majority of them were published in Russian Jewish periodicals or in the general Odessa press which enjoyed a large Jewish readership.

Sholem-Aleichem’s way of writing in Hebrew and in Russian was very close to his Yiddish writings, although one senses that in the former he was linguistically limited. His creative work in Hebrew and Russian is closely tied to his Yiddish work. The Hebrew versions of his stories were sometimes an intermediate version which led to the definitive editing of his Yiddish version. And, just as the Hebrew story “Simla” later grew in a long Yiddish novel, Blondzhende shtern, we find in his Russian story “Sto Tycyach” (100,000) from the series “Tipy Maloi Virzhi” (Characters from the small bourse) (1892) the prototype for the Yiddish figure of Menakhem-Mendl. In the stories “Roman moei babushka” (My grandmother’s romance) (1891) and “Gora Reb El’yukima” (Reb Elyokim hill) (1893), Sholem-Aleichem struggled with the issue of Jewish romantic conflict, parallel to his Yiddish novels. His work in Hebrew and Russian in their reciprocal relationship with his Yiddish works await detailed research.

Knowing both languages, Sholem-Aleichem contributed to the translation efforts associated with his writings into Hebrew and Russian, as well as when others were doing it. It would be difficult to overestimate Y. D. Berkovitsh’s extraordinary service as Sholem-Aleichem’s Hebrew translator. He began translating Sholem-Aleichem in 1905 and later prepared the three-volume edition of Sholem-Aleichem’s writings in Hebrew, which was published in Warsaw (1911-1913). Sholem-Aleichem also participated in the work, and in several texts, such as Tuvya haḥolev (Tevye the milkman), he completed the Hebrew version at the same time as the Yiddish. This edition provided Berkovitsh with a foundation for the fifteen-volume edition of Kitve shalom alekhem (Writings of Sholem-Aleichem) (Tel Aviv: Devir, 1951/1952). Aside from the novels in his last period, which are also missing from the “Folksfond” edition, included in Kitve are virtually all of Sholem-Aleichem’s works.

In more recent years, Berkovitsh’s Sholem-Aleichem translations aroused on several occasions a sharp critique. The errors were mostly directed at the dated literary Hebrew, which is now considered stilted, and at his excessive linguistic purism. Some hold that, in comparison to the status of Hebrew prior to WWI, the contemporary spoken language in Israel has created new possibilities for colloquialisms in Hebrew which did not exist earlier and which are absolutely necessary for every translation from Sholem-Aleichem’s writings. Another, more essential issue is connected here. Sholem-Aleichem’s simple figures in his Yiddish works often became in Berkovitsh’s translations “elevated” thanks to their “learned” speech, built on a vast selection of traditional sources in Hebrew and Aramaic, much higher than their primer-level in Yiddish. Thus, in recent years, a series of efforts have been made to translate Sholem-Aleichem into Hebrew. Among them in book form, the following have been published: Aryeh Aharoni, trans., Shalosh almonot, monolog (Three widows, a monologue) (Tel Aviv: Alef, 1969), 50 pp., Shiva sipurim (Seven stories) (Tel Aviv: Alef, 1973), 104 pp., Sipure elef laila velaila (Stories of 1,001 nights) (Tel Aviv: Alef, 1976), 79 pp., Menaḥem-mendl bevarsha (Menakhem-Mendl in Warsaw) (Tel Aviv: Alef, 1977), 229 pp., Sipure harekevet (Railway stories) (Tel Aviv: Alef, 1979), 210 pp.; Motl ben peysi haḥazan (Motl, the son of Peysi the cantor) (Tel Aviv: Alef, 1980), 264 pp.; Dov Yarden, trans., Sipurim ḥadashim (New stories) (Jerusalem, 1974/1975), 2 vols., including several stories translated from Russian. In all of these volumes are works that Berkovitsh did not include in his Hebrew translations. Motl ben peysi haḥazan in Uriel Ofek’s translation (Jerusalem: Keter, 1976), 167 pp., as well as Aryeh Aharoni’s translation of this work, were attempts directly to vie with Berkovitsh’s translation. It should be noted in passing that, while Sholem-Aleichem was still living, he was translated into Hebrew by Bialik and Yosef-Ḥaim Brenner.

In 1903 Sholem-Aleichem himself translated a story of his from Yiddish into Russian, and the novel Moshkele ganef was that same year translated from a Yiddish manuscript “under the editorship of the author.” Both were published in Voskhod. He took an active role in preparing a collection of his writings in Russian, which in 1910-1914 appeared in eight volumes in a translation by Yu. Pinus, as the “only” authorized translation of his works in Russian. Sholem-Aleichem’s correspondence with the translator remains extremely important for the very problem of translating his writings into foreign languages. The eight volumes were designed for non-Jewish readers as well, as Sholem-Aleichem instructed his translator to omit all specific mentions of Jewish ways, prayers, and the like, which had no direct Russian equivalents. And, indeed, the translator excelled at these omissions. Subsequent translators of his works into Russian left in place the Jewish specificities, usually providing glossaries with explanations. This was the method used in the two six-volume Russian editions of Sholem-Aleichem’s writings (1959-1961, 1971-1976). His writings have been translated into Judezmo, Judeo-Uzbek, Judeo-Tat, Alsatian Yiddish, Esperanto, as well as practically all European languages, Persian, Japanese, and Chinese. Some of the problems with the Hebrew translations were also true for other languages. And, the problems that Sholem-Aleichem himself saw in the context of the Russian translations were equally valid for non-Jewish languages. It is not simply a question here of specific Jewish practices and the rich stratum idiomatic to Sholem-Aleichem’s work. The difficulties also emerge when one is about to translate elements of his humor, such as, for example, language parasitism, intentional deviance in neologisms from the linguistic norm, various sorts of “manipulation” and “citation” of Yiddish dialects and of the languages that Yiddish speakers in his writings come into contact with, such as Hebrew, Aramaic, Russian, Polish, Ukrainian, German, and later English as well. Many of these important elements are necessarily lost in translation into Hebrew, German, and the Slavic tongues, and also in translations of Sholem-Aleichem’s writings on American topics in English. From here originates the widespread opinion that it is terribly difficult and perhaps impossible to translate Sholem-Aleichem in an adequate manner. From here also arises the altogether distinctive interest in research on Sholem-Aleichem translations.

Bibliography

- Biography

The Sholem-Aleichem bibliography—of his works and about him—is for the time being a task for the future. Efforts have been made at partial bibliographies, and the majority of them may be found in: Shlomo Shunami, Mafteaḥ hamafteḥot, bibliografya shel bibliografyot shel yisreeliyot (The key of keys, a bibliography of Israeli bibliographies) (Jerusalem, 1965), entries 4139-4149. One can add to this: Zalmen Reyzen, Leksikon, vol. 4. There are many autobiographical elements, transparent or hinted at, in Sholem-Aleichem’s work. He indicates this in his autobiography (until early 1881) Funem yarid (From the fair). Autobiographical in a direct way is also a major part of his volume Yidishe shrayber (Yiddish writers). The materials collected in Dos sholem-aleykhem bukh (The Sholem-Aleichem book) also have considerable biographical value—edited by Yitskhok-Dov Berkovitsh (New York, 1926), second edition (1958), 381 pp. Berkovitsh also summarized the material together with memoirs and critical evaluations in his Harishonim kivene adam (Our forebears as human beings) (Tel Aviv, 1938-1943), 5 vols., new edition (1959)—Yiddish translation as Unzere rishoynim (Our forebears) (Tel Aviv: Hamenorah, 1966), 5 vols.; for the Yiddish edition, Ts. Tsepilovitsh compiled an index (Tel Aviv, 1975). From the vast memoirist materials published, we can point to: Volf Rabinovitsh, Mayn bruder sholem-aleykhem, zikhroynes (My brother Sholem-Aleichem, memoirs) (Kiev: USSR state publishers for national minorities, 1939), 233 pp.; and Marie Waife-Goldberg, My Father Sholom Aleichem (New York: Schocken Books, 1968), 333 pp., Hebrew translation by Rut Shapira, Avi shalom-alekhem (Tel Aviv, 1972), 267 pp. In the wealth of materials to be found in the archives of the Bet Shalom-Aleikhem (Sholem-Aleichem House) in Tel Aviv, there are thousands of letters—his own and from others to him—a great number of them unpublished. The most important publications of Sholem-Aleichem’s letters: Y. D. Berkovitsh, in Tog (New York), in Haynt (Warsaw) (1923-1924), in his books mentioned above, and in Dos sholem-aleykhem bukh; and Oysgeveylte briv (1883-1916) (Selected letters, 1883-1916) (Moscow: Der emes, 1941), 322 pp. Many of his letters were published in books and periodicals in Yiddish, Hebrew, and Russian. A partial bibliography of his published letter collections may be found in Uriel Weinreich, ed., The Field of Yiddish (New York, 1954). Sholem-Aleichem’s manuscripts and letters may also be found in libraries and archives in Israel, the United States, and the former Soviet Union.

Sholem-Aleichem’s writings published during his lifetime, if not earlier published in the Yiddish periodical press, have been noted above. The first collection of his writings was Alle verk (Collected works) (Warsaw: Folksbildung, 1903), 4 vols.: (1) “Der ershter aroysfohr” (The maiden voyage), “Dos meserl” (The pocket knife), “Tevye der milkhiger” (Tevye the dairyman) (including “Dos groyse gevins” [The big jackpot], “A boydem” [Fizzled out], “Haytige kinder” [Children today]), and “Afn fidel” (On the fiddle), 195 pp.; (2) Mayses far yudishe kinder (Stories for Jewish children) (“Khanike-gelt” [Hanukkah money], “Baym kenig akhashveyresh” [With King Ahasuerus], “A fershtehrter peysekh” [A spoiled Passover], “Leg-boymer” [Lag B’omer], “Di fohn” [The banner], “Rabtshik, a yidisher hunt” [Rabtshik, a Jewish dog], “Mesushelekh, a yidish ferdl” [Methuselah, a Jewish horse], “Der zeyger” [The clock]), and “Sender blank un zayn gezindel” (Sender Blank and his family), 267 pp.; (3) Zelik mekhanik (Zelik the mechanic), “Hekher un nideriger” (Higher and lower), Blumen (Flowers), and Kleyne menshelekh mit kleyne hasoges (Little people with little ideas), 172 pp.; (4) Stempenyu (Stempanyu), 131 pp. Similarly, the “Tageblat” edition of Sholem-Aleichem’s works of 1912 (New York) as a rule used the same format, as well as some pamphlets from the “Familyen biblyotek” (Family library) series. The “Folksbildung” (Popular education) edition was actually a selection of Sholem-Aleichem’s published writing through 1903 in periodicals, books, and pamphlets. Sholem-Aleichem revised some of the works included, often in a rather radical way.